About a month ago, I took Miru to the Tierpark Berlin. When we entered the large park, she had no expectation and did what she does best: smiling at the guys who checked our tickets and nagging for a candy she sees in the hand of an other child. I, on the other hand, had great expectations because I had imagined her face as she would see, for the first time, monkeys, giraffes, elephants, flamingos, or tigers.

The first animals that captured her interest were the bison at the entrance of the park.

“Hobbelpaard!” she hollered, pointing at the magnificent grazers at the other end of the field. Hobbelpaard means rocking horse in Dutch, and it is her term for just about every ungulate.

The bison were far away and couldn’t have been that impressive to her, so my expectation rose even further and I chuckled.

“Just wait for the big wild animals, little one…”

We continued toward a birdcage with large exotic specimens of species I had never heard of. Miru was thrilled by the birds and I waited next to her.

In the heart of the Tierpark there is a mesh dome enclosing the habitat of some adorable lemurs. After chasing them for a while, we headed for the exit and one lemur slipped into the lock where I gently push it back into its enclosure. An older lady scolds me for no apparent reason and I retort with something ugly. Realizing any symptom of a short temper could undermine my vision of proper fatherhood, I hastily exited the lemur’s domain and headed for the monkey house.

In the heart of the Tierpark there is a mesh dome enclosing the habitat of some adorable lemurs. After chasing them for a while, we headed for the exit and one lemur slipped into the lock where I gently push it back into its enclosure. An older lady scolds me for no apparent reason and I retort with something ugly. Realizing any symptom of a short temper could undermine my vision of proper fatherhood, I hastily exited the lemur’s domain and headed for the monkey house.

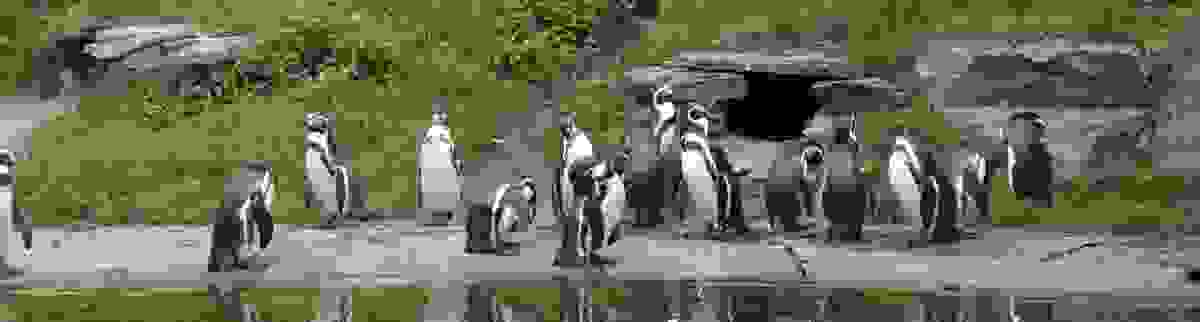

We have seen, among others, polar bears, penguins, Shetland ponies (another hobbelpaard), crocodiles, giraffes, tigers, rhinos, baboons, zebras, kangeroos – a large enough variety little Miru couln’t register let alone appreciate the exciting diversity of the fauna presented to her. It was time to go.

How will she remember that visit to the zoo at age two and a half? Is it ethical to intrude, or consciously try to create, her future memories of the event? I carry along shreds of memory from the time I was her age, and I suppose so do you, dear reader. I see a walk on the forest floor and I’m gathering pine cones. I see my parents and I know they weren’t at that moment trying to create that very memory, endearing as it is now. But the thought of actively influencing your offspring’s memories is not easily abandoned. Once we start asking, on behalf of our children, “how would they remember this?” that question imposes itself on every occassion. Should we direct our children’s biography while they are still unaware if it, or is that an indecent thing to do? And if we don’t want to feel like the directors of our children’s future childhood memories, how can we suppress it? Once we’ve let the genie of such seemingly innocent questions out of the bottle, there is no way back. We usurp it and it possesses us. Our mode of being is such entanglement.

How will she remember that visit to the zoo at age two and a half? Is it ethical to intrude, or consciously try to create, her future memories of the event? I carry along shreds of memory from the time I was her age, and I suppose so do you, dear reader. I see a walk on the forest floor and I’m gathering pine cones. I see my parents and I know they weren’t at that moment trying to create that very memory, endearing as it is now. But the thought of actively influencing your offspring’s memories is not easily abandoned. Once we start asking, on behalf of our children, “how would they remember this?” that question imposes itself on every occassion. Should we direct our children’s biography while they are still unaware if it, or is that an indecent thing to do? And if we don’t want to feel like the directors of our children’s future childhood memories, how can we suppress it? Once we’ve let the genie of such seemingly innocent questions out of the bottle, there is no way back. We usurp it and it possesses us. Our mode of being is such entanglement.

It surely is something we could never learn from the animals.

Miru and I eat in a bakery. She sits opposite to me. She likes animals and in the weeks after our visit to the zoo she begins to imitate them.

“Vogel” (bird) I say to her and she moves her arms like wings.

“Leeuw” (lion) I propose and she roars.

“Poes” (cat) makes her meow.

“Vis” (fish) I continue and she puts her hands together and sways them as if they were a goldfish. She laughs out loud. I feel the happiness in my throat.

Zelfs al zou Miru zich de gebeurtenis zelf niet meer goed kunnen herinneren, als zij terugdenkt aan haar jeugdjaren zal haar altijd een gevoel gewaar worden van geluk, van plezier en fijne dingen doen samen met haar vader (ouders). Dat is denk ik het belangrijkste, want veel dingen kun je je echt niet meer herinneren als je jaren later terugdenkt…. Maar je weet vaak nog wel hoe je je voelde in die tijd, met die mensen om je heen, toch?

Zo’n vader als jij zouden meer kinderen willen hebben!