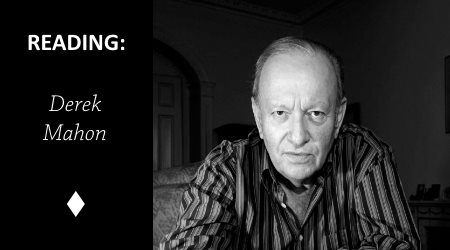

We travel to Northern Ireland. Derek Mahan (b. 1941)’s poetry has been compared to Louis MacNeice and W.D. Auden. Some critics have called it ‘too controlled’. I found this poem worth reading, with an attribution to yet another famous Irish poet:

Lives

(for Seamus Heaney)

First time outI was a torc of goldAnd wept tears of the sun.That was funBut they buried meIn the earth two thousand yearsTill a labourerTurned me up with a pickIn eighteen fifty-four.Once I was an oarBut stuck in the shoreTo mark the place of a graveWhen the lost shipSailed away. I thoughtOf Ithaca, but soon decayed.The time that I likedBest was whenI was a bump of clayIn a Navaho rug,Put there to mitigateThe too god-likePerfection of thatMerely human artifact.I served my maker well —He lived longTo be struck down inDenver by an electric shockThe night the lightsWent out in EuropeNever to shine again.So many lives,So many things to remember!I was a stone in Tibet,A tongue of barkAt the heart of AfricaGrowing darker and darker . . .It all seemsA little unreal now,Now that I amAn anthropologistWith my ownCredit card, dictaphone,Army-surplus bootsAnd a whole boatloadOf photographic equipment.I know too muchTo be anything any more;And if in the distantFuture someoneThinks he has once been meAs I am today,Let him reviseHis insolent ontologyOr teach himself to pray.

Alright, 1854-2000 = 146 BC: The Battle of Corinth. The “I” was something buried with the dead, a torc of gold in the first instance. That riddle was fun. The oar in the shore happened probably in ancient Greece as well, given the reference to Ithaca.

I found that the Navaho covered the eyes of the dead with some clay. That gives away what Mahon wants to say, that the ‘thing’ is mitigating the god-like perfection, in a way.

The lights going out in Europe never to shine again could refer to the holocaust, if his ‘maker’ is god? Struck by an electric shock in Denver? We might be missing something here.

With Tibet and Africa (heart of darkness) he makes this truly international. But now he is an anthropologist, who feels it is unreal, all these many things to remember. So he is not anything anymore, a rather existentialist anthropologist.

How does he pay respect to all these things, representing all these many lives that were lost and buried with gifts that have lost their meaning? He demands that a future generation don’t identifies with him, it sounds like he wants to break a chain. Or, and he might be well aware of the fact that such is impossible. In that case that future person should teach herself to pray. Indeed, the ontology he describes, the one in which you become the stuff the dead are remembered by and are at some point reduced to such a thing yourself, is insolent and ultimately nihilist. And that is of course why he turns to prayer.

This is a strange enough poem, and I have the feeling there are some more things to be dug up here. Any suggestions?